Kitty Little

Hello!

I’ve been taking a break from climate change and working on my book: Kitty Little, a memoir-led social history based on my mum’s diaries.

Thanks for reading,

Tanya

CW: suicide.

It took me thirteen years, after her death, to gather the courage to read my mum’s diaries. I read them in fragments, over the course of a year.

She took her own life, and obviously her death was tragic and heart breaking, full of regrets and guilt. I assumed her diaries might be harrowing and introspective, but they aren’t. They are filled with humour, sarcasm and intelligence and - surprisingly - incredible details of what life was like as a young woman in the 60s, as the morality of the 50s collided with the emerging freedom of music and politics.

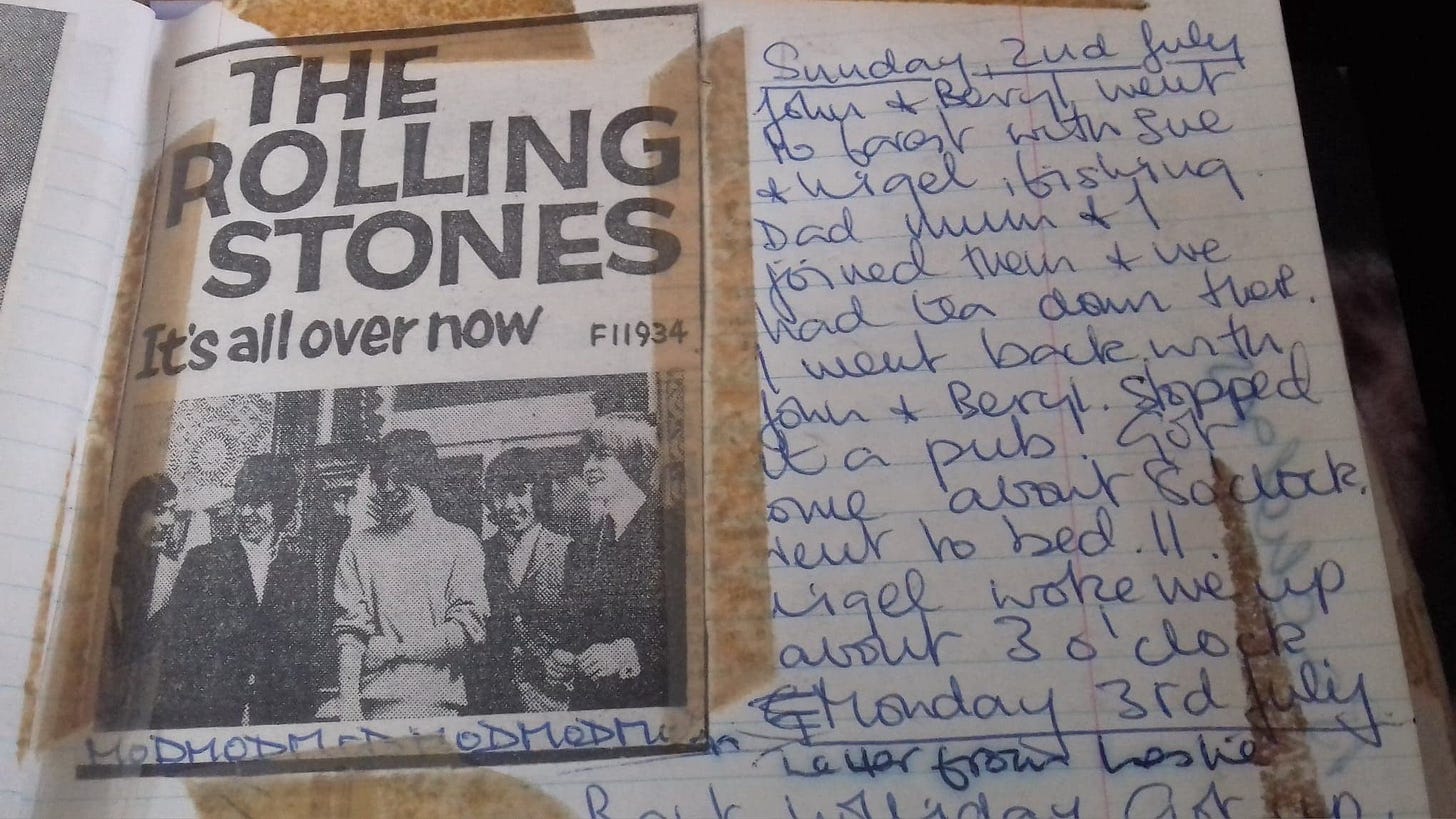

There’s the blue lace stockings that she bought when she was nine months pregnant. The hitchhiking, the bands she sneaked off to see: Thin Lizzy and The Stones. The boredom of school. The arrests. The beatnik subculture.

My mum was pregnant at seventeen and was sent away to have the baby. There are two diaries that document nearly every day of the pregnancy and the horrendous way the girls in the convent were treated, their babies forced into adoption. Despite the claustrophobic social pressures, my mum and the other girls give birth, smoke fags out of the windows, hide booze under their beds and flirt with the workmen. They cry and support each other when their babies are taken away, and rage at the injustice of it all.

Her baby - my sister Julia - contracted meningitis resulting in a severe learning disability. Later diaries depict life in the seventies, raising children, struggling to fit into the world of her husband (my dad) and his large Irish Catholic family dotted around our street and estate: a complex mix of supportive community and crushing morality. The final few diaries expose the cruelty of my mum’s invisible illness: M.E, the dismissal of the medical establishment and indifference of society to her loneliness and desperation.

I’m holding these pieces of social history in my hands, full of love, teenage rebellion and a lifelong struggle for recognition and freedom. There’s so much here: the sexism, the struggles to survive disability and poverty, the classism, the way the medical profession and wider society treats girls and women. But they find ways to fight back, to survive. It’s a story of courage from working class girl, who deserved to be treated better.

Kitty Little

A diary

1964

Name: K.I.Little

Age: 16 yrs 10 months

Address: 19 Pauntley Rd., The Scarr, Newent, Gloucestershire

Likes: Boys. Fags. Money.

Dislikes: Whisky. Getting up. Work

Born: Bristol

Date: June 24 1947

Aim in Life: To marry a Rolling Stone

Kitty: Saturday 29th May 1964

Moses came back today. I think everyone gets a kick out of telling me. Was going to go to Cheltenham to get some shoes, but asked Eddie if she’d go to Bristol instead. We started hitching about 3.30, got a lift just past the bridge. This chap was a photographer or something, and reckoned he knew Tom Jones and John Lennon and some others. Anyway, when we were near Bristol he said would we be interested in doing some modelling? We said perhaps. Then he said it would be in the nude, probably just the bust. He said he’d have to go down some lane to look us over first. I was killing myself in the back, it was so ridiculous that he’d expect us to do that.

Kitty: (Nearly a year later) 21st March 1965

I am almost sure that I am going to have a baby. What I don’t understand is why I don’t feel more worried, probably because you only worry about things you should not have done. That’s not how I feel. I have no regrets. I feel no sense of shame.

Tanya: 22nd November 2006

A death. An inquest. A long wait for mum’s door keys and a kind interview with the police. They explain that my my mum killed herself and was found in her bed by the police after being alerted by a friend. I can imagine the scene through her ground floor maisonette window: A crocheted bedspread; terracotta paint over the wood chip wallpaper; the framed picture of the Birth of Venus by Botticelli, looking down at her; maybe one of her four cats asleep on the bed.

The suicide note, I presume, was next to the bed, but no one gave me the exact details. The note I have is a photocopy. The words are thoughtful and, as always, focused on her children, sparing our feelings.

‘Absolutely no one could have prevented this.’

I disagree. Fourteen years after your death I hold in my hands seventeen diaries, some in your fast-paced teenage handwriting, full of tributes to the Rolling Stones and real-life boyfriends. The later diaries are a more serious account of parenting us in the 70s, unexplained illnesses creeping into the pages. The diaries just before your death contain short, frustrated sentences and patchy information.

There’s also a box of letters. Some from us, your children, the rest from a wide network of friends from all across the UK who suffered in similar ways to you. There’s a photo of you holding your first baby. You are eighteen, the same age as my daughter is now.

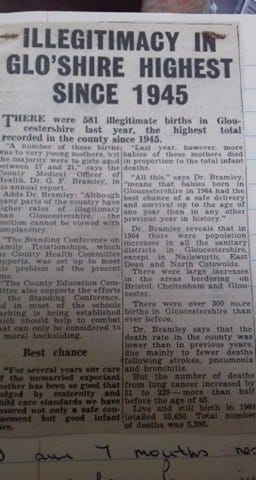

Sellotaped in the pages is a faded article from the local Gloucester newspaper dated the 5th September 1964: ‘Illegitimacy in Gloucester Highest Since 1945,’ leveraging the world war II end date for gravity. The piece laments the ‘moral backsliding’ of the ‘unmarried, expectant mothers.’

Tanya: 19th November 2006

I’m busy. Running into the house for something, my phone, or a work notebook, I forget. I’ve just dropped my four year old at her dad’s house. The phone rings as I’m racing up the stairs, so I swivel round and run back down.

‘I think mum is dead. I think she’s killed herself.’

In the next twenty minutes I’m at my friend’s kitchen table, who says ‘We’ll break a house rule for once,’ and passes me a roll-up which I smoke intensely. Her boy and girl stare at me and I try to be normal in front of them. I’m not crying, but I feel blank and stunned.

The next week consists of: waving goodbye to my daughter; a four hour train journey to Gloucester; a stay at my dad’s flat while I wait for the police to release the keys to mum’s maisonette and finish whatever it is they do; pace, pace, pace around my dad’s small living room. Waiting is painful, gritted teeth and chewed mouth, pounding the streets of Gloucester to avoid conversations that speculate about the imagined scene of my mum’s death: ‘I saw it coming/I always said this would happen/Just a matter of time/I bet it was an overdose.’

Two days later and the interview with the kind police officer who hands me the photocopied suicide note and mum’s door keys attached to plastic picture of an angel with white wings and a halo. At last, I have something to hold that has been recently held by her hands. Sitting alone on a bench in Gloucester Square, surrounded by people and prams and pigeons, I read the note over and over and grip the keyring.

Kitty: Saturday 19th June 1965. Aged 17. (A letter never sent)

Dear Jo,

Did you see a programme on television about unmarried mothers and adoption, on Tuesday? If you did you might be able to understand how I’m feeling just now. I seem to keep cheerful during the day, at night I break down and cry for hours, I wake up with red eyes every morning, by night time it’s gone and the next morning I look washed out like something out of a nightmare.

I suppose this is the most self-centered, sickening, self pitying letter you’ve ever received, but when I hear people moaning about their boyfriend troubles and raving about pop groups, I feel I could gladly cut their throats. In a way I suppose it’s a kind of superiority, a sort of ‘my problem is bigger than yours’ attitude, but at the moment I seem to think everyone should grow up, somehow.

At night awake in the dark I sort of play games and imagine I’m going to have my baby and I sort of watch as it’s being delivered and hear it crying. It’s always a girl, all tiny and fragile. Then later I see the nurse who delivered it and I ask her for it but she says it’s too late, that I said I didn’t want it so they’ve taken it miles and miles away where I’ll never find it. That part makes me cry terribly.

Have you ever hated someone, really hated them? I think when love turns to hate, it’s twice as bad. Moses could have seduced anyone in the world, but it shouldn’t have been me, it really shouldn’t.

Everything seems to be moving so fast now it’s frightening. I have an appointment with a welfare worker to interview me and Moses if they can get hold of him. We’ll both have to have medical examinations, so that the adopters don’t pick up anything. Then 6 weeks before the happy event I move to a jolly common-to-all home in Cheltenham where all of us unfortunates give birth to our bastard babies. Three months later I sign a document legalising everything, after that the child is no longer considered mine, I’ve no longer got legal access to it. I’d rip up this sentimental rubbish if I were you.

I just wanted someone to know how I felt under this hardworking office girl exterior. I’m paying for my abuse of sexual morals, not the baby, nor Moses. The whole bloody lot’s fallen on me.

P.S. do send me a card on Thursday. You can imagine how overjoyed I’m going to be to be 18.

Love Kitty.

Tanya: 1995 King Alfred’s College, Winchester

I’m studying history and I learn of the importance of diaries as a primary sources. In history you look for the motives of the author and assess the evidence against the context of the time. You even assess the analysis of other historians as a secondary source. As the narrator of this history no doubt I’ll bring my own values and biases.

Diaries are everywhere now. Everyone is a pundit, a diarist. Daily habits, routines and photos scroll past us constantly, the familiar updates of everyday people, instant, fast, funny, tragic, written for friends, colleagues and the general public. Historians, cultural theorists and anthropologists, just as with historic paper diaries, will be trawling through the roar of personal stories searching for the missing voices, the pauses in the noise, the gaps in the evidence.

My mum’s voice is an unusual source for a historian to work with. A missing voice. A working-class girl, growing up in a market garden. Her mother was from a south Wales mining family, of the ‘Welsh Not’ generation. My nana was ambidextrous, a word I was fascinated by. Her teachers tied her left hand behind her back to force her into right-handedness. I would try, and fail, to hold my right hand behind my back to see if I could force myself into left-handedness.

My nana was in service from the age of fourteen, her bed in the basement of a large townhouse, its legs in pots of jam to stop the insects crawling up, so I was told. She married my grandfather who then went to war, returning a hero with a German sword and six medals — trophies that hung on the wall of their farmhouse.

They were busy and hardworking. Up at dawn pricking out celery and weeding leek beds on their seven acre plot. There was little time to spare for a young girl and so Kitty became resourceful at solitary play, reading, and later on sneaking off with friends in search of boys and bands.

At seventeen my mum became one of the one and half million teenage girls and young women who were coerced — or more often forced — into giving up their babies during the 1960s. It’s a familiar story we now know from films like Philomena, full of tragedy, redemption and lost and found children.

My mum changed history for poor women, although she didn’t know it. She fought for the right to keep her baby. Not as a campaigner, but as a person who bucked the trend. All of those people who didn’t conform helped change the trajectory of society. They are the hidden voices of history. And sometimes they paid a high price for their defiance and rebellion.

Tanya: Gloucester, Longlevens Estate, 1980 Age 9

My mum speaks to us in French over our cornflakes. She draws out the accent theatrically, and ends with ‘Ooooh, la la,’ pretending to smoke a cigarette. These are the French words I remember: ‘Je T’aime. Comment t’appelle tu? Excuse moi.’ The words my mum made into a game as she brushed our hair.

My mum only went abroad once, on a school trip to Finland but she loved everything culturally European. Cheap prints of Van Gogh’s sunflowers, Renoir’s blue-green ponds and Rembrandt’s dark shadows hung on the walls of our council house. In the evenings she played us Moonlight Sonata, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and the Flight of the Bumblebee, and my all-time favourite: Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture ‘with real cannons’. I knew that Beethoven was deaf and that Mozart wrote a whole symphony when he was a child. When we went to bed, she got out her Rolling Stones’ albums and read James Herbert’s horror stories, accompanied with a couple of barley wines and cigarettes.

Ours was a solid, white council house, with a flowering garden and a drooping, golden laburnum tree in the centre. Our street was dotted with our wider family, Irish Catholics on my dad’s side. My grandparents lived next door and two other sets of aunties, uncles and cousins a few doors away. The bleeding heart of Jesus looked down at us from their doorways, and little plastic bottles of holy water from Lourdes were passed around as a remedy for everything. We were reminded constantly and solemnly that Jesus died for our sins.

My mum wasn’t a Catholic, but she sometimes too us to mass on Sundays at St. Peter’s church, an improbably beautiful monument amongst the increasing number of ‘Cash for Gold’ and betting shops, whose doorways now shelter Gloucester’s growing homeless population. She loved the meditation and the incense of Mass. The murmur of in nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti took her away from the noise and demands of domesticity for an hour.

She never weighed much more than 7.5 stone and I barely ever saw her eat. Sometimes she sat with a teacup and saucer with two yellow pills next to her, at breakfast. She was always cooking for other people, though, and weekends were a merry-go-round of curry and rice, bolognese or roast dinners. This was until I was around eleven or twelve years old. After that, redundancy for my dad from his foundry, midnight rows, free school meals and a divorce. Just after she and my dad split up, she gave up the cycle of churning out fresh cooked meals and instead stuffed the freezer with Findus Crispy Pancakes, reluctantly withdrawing from us and spending more time in bed, trying to recover from an illness that I didn’t understand.

Kids are different today, I hear every mother say

Cooking fresh food for your family’s just a drag

So she buys an instant cake and she burns the frozen steak

And goes running for the shelter of her mother’s little helper

Mother’s Little Helper — The Rolling Stones